With the news that the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi has left this world, I'm posting scenes from a novel-in-progress that describe encounters with the man. Enjoy...

Fiuggi had been taken over by the Maharishi’s entourage and hundreds of transcendental meditators. Lee’s contact was the press officer of the operation, a young German baron, gracious and eager to introduce her to the spokesman for His Holiness, not so keen on the possibilities of a meeting with the Maharishi himself.

“You will please, this afternoon attend darshan. After that, we will talk more. Come. You must rest from your journey."

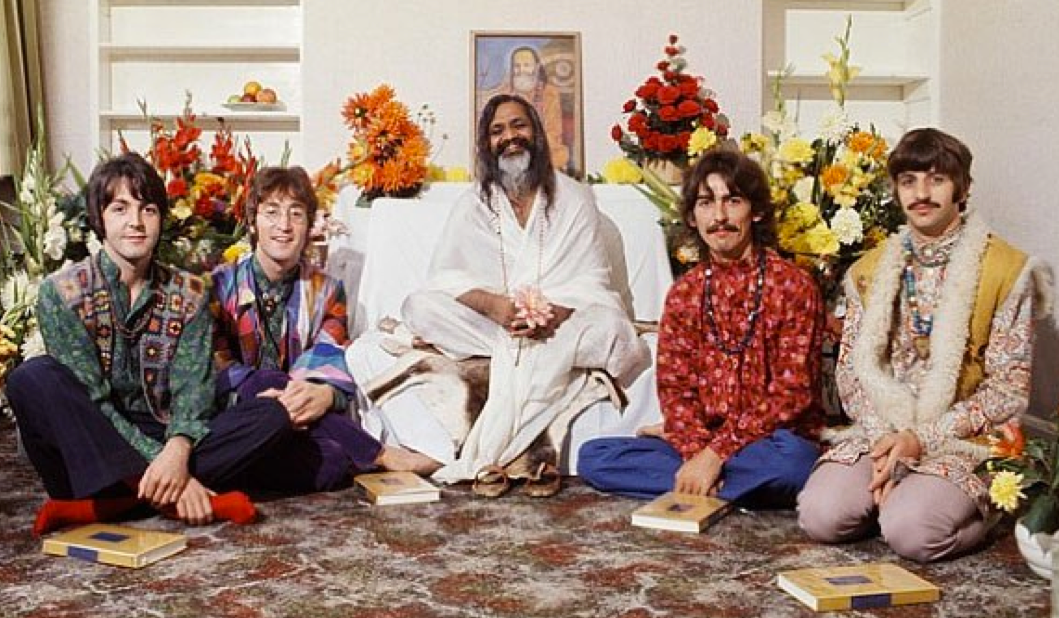

They were assigned a simple room in a private house, all the town’s public accommodations having been filled with young Europeans and Americans who spent their time meditating in their rooms, coming out only for meals and for darshan, the sessions when the Maharishi sat on a deerskin, surrounded by flowers, answering questions and leading group meditations.

As Lee and Joe were escorted to front row seats by the baron, the Maharishi beamed at Lee, pressed his palms together, and nodded. “Jai guru dev jai guru dev jai guru dev."

She returned the little man’s gesture and looked her question to the baron, who whispered that he would explain, later.

“Maharishi, you have said that anyone who meditates will become better at what he does. But what if the person is a thief?" Lee turned to see that the Scandinavian-accented question was from a tall blonde in a sari.

The guru seemed pleased, a star batter swinging at a home-run pitch. “To be a better thief is no longer to be a thief." The assemblage laughed quietly.

“Maharishi, there is criticism in the press, especially in this Catholic country, that the west has its own religions, that Eastern religions are not needed here. How do you answer those critics?" The questioner was a teenaged boy who spoke with the hard r’s and flat a’s of Chicago. “How do I answer my parents?"

There was louder laughter and what felt like a collective leaning forward. The tiny dark-skinned man in white robes, surrounded by pale Western faces, was silent a moment. He was not, Lee thought, looking for an answer but considering how much to say of what he was thinking.

“Western religions teach, Be good and you will see God." Another silence. “It is very difficult to be good." The listeners murmured their agreement. “Eastern religions show you God." A small smile and a twinkle. “It is then quite difficult to be bad."

Lee took in a gulp of air at the realization that this might be the truest thing she had ever heard. The glowing place of rightness that she entered with her mantra was affecting everything, making it easier to do what was right to do, even when she was frightened. Joe too was seeing God and it had become difficult to be that other Joe. Not impossible, she realized, just difficult. But with more meditation, more time with God, it might become impossible.

After more questions and answers that she missed in her thoughts about the effects of seeing God, the Maharishi led a meditation and then was escorted away. The young German began to talk about arranging a meeting with Jimmy, the Maharishi’s Number One. She touched his arm. “That was the deepest I’ve ever gone in a meditation. Is it him or being with all these people? Or was it what he said—about seeing God?"

“It was perhaps all those things. Perhaps it was also that he was giving you a special blessing. I have never heard him greet anyone as he greeted you."

“All that jaigurudeving? He could have been greeting a TM baby. This prgenancy started the week after we began meditating." She began to say that meditating seemed to have been the key, but seeing Joe’s frown she decided not to give the wise little man any credit there.

That evening they joined Jimmy and the rest of the inner circle for dinner at Jimmy’s villa, a lovely old place with exquisite tile floors and a courtyard filled with flowers tumbling out of pots and boxes and beds. Clearly Jimmy, a balding American in a business suit, was one important fellow in this realm.

The Maharishi, Jimmy reported, would like to talk with her in Boston in July. Would she be available? Everyone seemed to think this was marvelous. But she had already come to Fiuggi. Ah, but Thursday, tomorrow, was a regular day of silence for everyone, and His Holiness had decided to stay in silence himself for the next six weeks.

Joe immediately began to negotiate with Jimmy, asking if a large donation would get the guru to look at Lee’s proposal now.

“He doesn’t have to look. He says she’s the right person to do the book. I’m to give you the addresses and phone numbers of any transcendental meditators you would like to interview and he’s recommended several well known people who might be very interesting to readers."

Joe began to say more but Lee thanked Jimmy warmly and tugged Joe toward the buffet.

“I bring you half way around the world and the little creep stiffs us? I don’t believe it."

“No, no, really, I’ve got what I wanted. Without talking to him. In Boston, I’ll interview him and ask him to write a foreword." She surveyed the impressive array of vegetarian dishes, spooned pasta in a green sauce on Joe’s plate and her own. “Lovely. It’s basil. Mmm and garlic. Smell."

While Joe read through Jimmy’s magazines, Lee talked with a rock guitarist from Belfast, a French nuclear physicist and Bunny, a short, graying heiress who would be hosting the Maharishi in Boston. Bunny had already decided which of the 14 bedrooms in her house would be Lee’s. It was all set.

Lee approached the most exotic person present, a tall brown woman swathed in bright colors and patterns, from her wrapped head to the belled hems of her silk palazzo pants. She was, Lee discovered, an American dancer named Jamuna, now the Maharishi’s driver. Best of all, she had been in a road company of Boobs and was delighted to share stories about Marshall Poole as she and Lee ate peanut butter cookies and sipped cardamom tea.

When Lee and Joe began making their good-nights, Bunny and Jamuna stopped them.

“You have a car here?" Jamuna was talking very quietly.

“Yes, of course."

“No one has cars here," Bunny whispered. “Except Maharishi. Are you going back to Rome tomorrow?"

After months in Fiuggi, the women couldn’t take another silent Thursday if playing in Rome was a possibility. With the boss going into seclusion, and having no need for his driver, they figured they could get away with a quick disappearance. The tiny Maserati, they insisted, was not a problem.

“We’re both very skinny." Jamuna pressed the volumes of cloth close to her sides to demonstrate. Bunny, all bones in her trim gabardine pants suit, laughed. “We’ll fit quite easily behind the seats."

Joe agreed graciously, pleased, Lee thought, to aid and abet in the breaking of some of the “little creep’s" rules. He would have the hotel make up two beds in the sitting room of their suite. No problem. They were his guests.

After breakfast the next morning, the two women wedged themselves, knees up, behind the Maserati’s seats, keeping their heads down until the car was well out of town.

Bunny and Jamuna knew a different Rome than Lee’s. Joe bowed out, leaving the three females to giggle their way through facials and shampoos at Elizabeth Arden, lunch at the Hassler, a sweep through the city’s most elegant shops, and a visit to a gypsy fortune teller Jamuna swore had saved her life. The dancer showed Lee an oddly marked amulet that the gypsy had given her, pulling it from the array of beads and scarves that swathed her neck above the sweeping, silk body draperies that fluttered around her when she walked.

Her head wrapped in purple, orange and red twists of cloth, her face broad and brown and beautiful, Jamuna was a literal traffic-stopper in Rome. Drivers hung out of car windows, veering toward oncoming trucks, causing much screeching of brakes. Cars waiting at red lights did not move after she floated past them and the light turned green.

On the narrow sidewalk that led to the gypsy’s house in Trastevere, the women walked Indian file, Lee bringing up the rear. A chubby bald man stepped into the street to let them pass and stared open-mouthed at Jamuna. As Lee passed him he was murmuring in wonderment, “Que bella negra!"

Jamuna reported to the bleached-blonde fortune teller that she’d been wearing the amulet as directed. Was she out of danger? The woman looked into her client’s teacup, studying the leaves intently.

“The evil forces have retreated but they are not gone. You will wear the amulet for three more months, but its powers must be restored."

For the payment of a great many lire, she would give Jamuna the needed instructions.

Lee was disappointed that the woman hadn’t asked that her palm be crossed with silver. When Jamuna handed over the bills, the gypsy wrote something on a small piece of paper. “Here, signorina. At midnight at next dark moon, two nursing women must sit back to back, one looks north, one looks south. They must each put milk in silver cup. You must put amulet into cup and say words on paper."

Jamuna, as nonchalant as if she’d just been given directions to the super market, pocketed the note and thanked the gypsy graciously.

“Bunny, don’t you have something to ask—about that problem on the Cape?" Bunny, in the dark suit and pearls of a proper Backbay matriarch, shifted uncomfortably on the hard kitchen chair. “Oh my goodness. I can’t think of a thing."

Jamuna turned to Lee, who shrugged, palms up. The gypsy stood to show them out, then looked intently at Lee.

“Boys. I see three boys, three men."

Back on Vittorio Veneto, Jamuna and Bunny introduced Lee to Café Hag, the first coffee Lee had drunk since learning she was pregnant. “Makes me too jumpy so it can’t be good for the baby and Sanka is disgusting, so I just gave it up." But Café Hag was both decaffeinated and delicious. Lee sipped and puzzled over the gypsy’s words. What did three boys and three men mean?

“You better figure it out, girl. That woman knows her business." Jamuna’s evidence was that the unseen evil forces had still not shown themselves in her life.

Lee thought that was kin to being grateful elephants hadn’t flattened your house in Cleveland. Joe did not want a boy. This baby was Kate and that gypsy was full of crap.

“Lee, promise you won’t ever tell Maharishi we went to a fortune teller. He would be just furious." Bunny seemed sincerely concerned. Lee responded, trying to be as serious, that she couldn’t imagine the subject ever coming up. Although if Jamuna managed to get two mothers milking at the next dark of the moon, the news just might get to him along the grapevine.

Snipped here: a description of the return drive to Fiuggi and some fabulous adventures in Italy—they don’t include the Maharishi so I cut them for this piece.

“Guess who’s meditating? Stefan!" Celeste, resplendent in fuschia pallazo pants and a purple jacket, giggled with delight as she hugged Lee and Joe at the Newark arrivals gate.

Joe stepped back from her embrace, frowning. “Where’s Das? He was supposed to pick us up. In our car."

“Oh, he’s outside waiting for you. But I just had to come and welcome you home and tell you the good news. Lee, you look fabulous."

“I love your news. Stefan meditating. That’s fabulous."

She would wait for their real conversation, for their inevitable phone connection to hear the real story, to ask how Celeste had managed to get Stefan to a TM meeting, to find out if he’d changed yet, as Joe had.

She would tell Celeste about the Good Joe who stayed present throughout the trip, if you didn’t count one bout of silent rage, and a few narrowly averted bad moments. Not once had he broken something, or threatened to fire her from her job as Signora Montagna.

Later, on the phone, she would tell Celeste what the Maharishi had said about seeing God and how much easier it would now be for Stefan to be good.

~~~

Lee eased quietly across thick Persian carpets in the massive, dark bedroom with the stunning view of blue water and gently gliding sails. Bunny’s grand old house on Marblehead Neck had emptied out, the Maharishi being off somewhere in Boston, Bunny and all the other house guests drawn along in his wake, every Chosen One determined to stay as close as possible to the Master. Still, Lee moved carefully, listening for sounds that would propel her instantly out of this room, the guru’s private space.

She wasn’t sure what she was looking for, some clue perhaps to who the renowned yogi was and what he was really up to, if that was not, as he said, the bringing of the dharma to the west, a gift, no strings, no hidden agendas.

She knew that he was bringing her the only calm times in her life, the daily sessions when she stepped away from any fear and anger, the times when Kate stopped tumbling and, with her, became peaceful. Lee was sure those moments of the days made it possible for her to do her best in all the others.

Snipped some plotting here—also not about Maharishi.

The previous evening, grateful for a breeze moving across Bunny’s park-sized lawn and onto the broad, roofed porch that encircled the house, Lee had been escorted to a wicker chair next to one in which the great little man sat, smiling. He had surprisingly expansive answers to all her questions about meditation and its effects, seemingly enjoying himself. When she came to the end of her questions, she closed her notebook and eased forward in her chair, thanking him for his time. He stopped her with his voice.

“You must prepare yourself for great changes that will not be easy for you. As they unfold, know that you are strong."

Of course. She was clearly adding an infant to her busy life. Still, she thought it kind of him to be so personal. He held his palms together, jaigurudeving her as she made way for the next seeker.

She looked around his room now for signs of his occupancy. There seemed to be none. No robe across a chair, no books or magazines on the tables, no papers or trinkets or personal effects of any kind.

She opened the closet and found only a row of handsome wooden hangers that bore no clothing. The drawers of an early colonial highboy held nothing but pomanders and lining paper.

The room was dominated by a canopied bed, a bed so high that three steps stood at each side to allow any occupants to reach the mattress. The linens were so startlingly white in this room of muted rugs and mellow wallpaper that Lee guessed they were all newly bought, for the Maharishi’s visit. She stepped into the bathroom and found there stacks of new thick towels and washcloths, all equally white.

The man wore only white. Maybe there was some rule that colors could not touch his skin. Maybe cloth that had touched other bodies could not touch his, so all linens had to be new. Maybe he didn’t require any of this and it was just Bunny and the other devotees knocking themselves out, hoping to please him.

At the bottom of the steps on one side of the bed, a pair of worn leather sandals was neatly aligned. Lee put a foot beside them and saw that they would be too small for her, wondered if the owner had gone off this morning shoeless, or perhaps owned two pair, a shocking excess.

Her eyes moved to the bedside table where a fat, tattered, hand-sized notebook sat next to a phone. It was undeniably personal and much used. She took a deep breath and opened it.

Page after page held names and numbers, country and city codes for people all over the world, each one entered in a small careful hand, the tidy effect spoiled by indecipherable notes that ran up the sides and at angles across each sheet. Paper notes were tucked everywhere, making the book bulge, its cut edge a full inch thicker than its spine. Lee turned the pages gently, making sure nothing fell out.

What would she say about this in her book about meditators? Nothing. She was not supposed to have such a thing in her hands. And the only question most readers would want answered was What are the Beatles’ phone numbers? Not something she would print, though she smiled, seeing several numbers by the name George Harrison, along with more of the Hindi notations. The guru’s notes to himself about this most spiritual of the Fab Four?

The phone rang, shrill in the silence, the sound of the outside world catching Lee in the act. She stared at it, wondering if the caller would know what extension was being picked up. Of course he/she wouldn’t. She lifted the receiver.

“Hello?"

“Oh thank goodness. I was afraid you’d be napping. Lee, darling, you’ve got to rally the pundits."

“OK, Bunny. And what am I rallying them for?"

“We’re at MIT in a computer lab. They’re letting Maharishi play with some contraption that does a visual printout of sounds. And he wants the pundits to come and chant into it."

“All right. What time do they need to be there?"

“Soon. It’s a half-hour drive, so get them organized and come along as soon as you can."

Lee wrote down Bunny’s directions for driving from Marblehead Neck to MIT, studied a map in the glove compartment of the minibus in the carriage house, revved the engine and pulled it out onto the gravel. At least six Indian monks were ensconced in the rooms above the cars. Being female, she could not enter their quarters to discuss her mission with them, which left her standing under the windows, wondering how to get their attention. Ahoy, pundits! did not seem respectful.

“Uhh, halloo? Gentlemen?"

She considered looking in the house for a dinner bell, but settled on calling up to the windows again.

“Maharishi says ‘Come now.’"

Discerning no movement or sound in the rooms, she considered barging in, rules or no rules. How good were these holy men at being celibate if they couldn’t handle being in the same room with a woman? Especially a big unsexy pregnant one? Maybe none of them spoke English and she was just making unintelligible noises. Maybe she’d have to use the Harpo approach and honk the horn.

The door at the bottom of the stairway opened and a round brown man with a walking staff stepped into the courtyard, smiling broadly. Lee opened the door of the little bus and, with a gesture, invited him to board. Six more Indians in white togas followed him at a sprightly pace, settling quickly into the seats of the bus, looking forward expectantly.

One way or another, she would deliver them to the boss. She just had to drive this thing into and across Boston although she’d never driven a minibus before and didn’t know Boston from Buenos Aires. But she’d studied a map, and she thought she had the gears figured out. She nodded to the pundit beside her and turned the ignition key.

Lee hadn’t calculated on the mental insularity of Marblehead Neck, the inability of highway engineers to communicate, nor on the madness of Boston drivers. The tiny island was hosting an enormous number of sailboats for a week of racing, but none of the boats must be manned by strangers—or they had all arrived by sea rather than land; signage was cryptic or nonexistent and Lee circled the island twice before finding the way off it to Marblehead proper. It was, she decided, like the price of a yacht—if you had to ask, you’d disqualified yourself. People on Marblehead Neck didn’t need signage to know where they were going.

Lee had memorized the major turns she needed to make, knew she had to bear west and southwest. Which made things dicey when signs with the right road names on them also carried the words north or east. She considered handing the map to the round brown fellow in the passenger seat but was deterred by the fact that he had said not a word to her and had looked neither left nor right but only directly ahead, since taking his seat.

Somehow the van arrived in center-city Boston, which Lee verified when they passed, as promised, City Hall Square. Every narrow, lumpy street in the city was filled with manic drivers, two of whom almost sideswiped the van as they darted through traffic at astonishing speeds. Once a Plymouth blowing off a red light would have rammed the bus broadside if Lee hadn’t slammed on the brakes, sending the pundits into tumbles of togas on the floor. Frozen in a sound wash of blasting horns demanding that she move on, Lee was astonished to find her arm in front of the passenger-seat pundit, protecting him from the dashboard. She checked her passengers, found them all back in their seats, smiling, totally unperturbed.

They were unshaken by the several near collisions, by the repetitions of passing landmarks as she struggled her way through the maze of narrow streets, by the godawful heat that had Lee drenched and sticking to the seat.

As they pulled up in front of the right hall at MIT, the pundit beside her turned to Lee and smiled. “Thank you, Mrs. Smashing fine day. Like Calcutta." There wasn’t a bead of moisture on him.

Lee gave him the hall name and room number and watched the group file toward what was probably the right building before setting off to find a parking place that would accommodate the minibus.

The half-hour journey had taken more than three times that. But the Maharishi was unperturbed, delightedly cueing the pundits into song at microphones on lab tables. When the printed patterns their voices generated were handed to them, they laughed like little boys, enchanted with this wondrous new toy.

Lee stayed on the edges of the spectators, not wanting to catch the Maharishi’s attention. She didn’t want to be identified now as the person who couldn’t handle such a simple task as delivering the pundits on time. This was no time for fouling up. In the weeks ahead she had a book to start and a baby to finish and Joe was going to be no help with any of it—she was on her own.